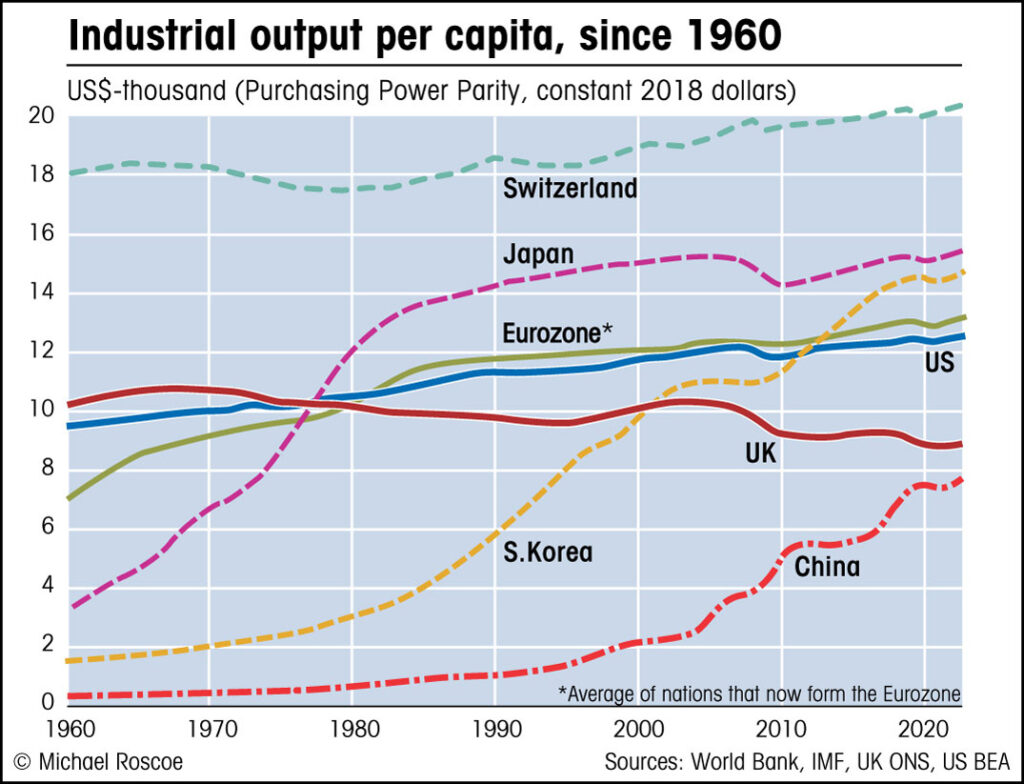

Not many people will have seen a chart like this before: it illustrates an aspect of economics that is rarely discussed or even thought about. But in fact, for reasons that I will explain, this chart shows something that is fundamental to wealth creation: a nation’s productive output in per-capita terms. In other words, it indicates a country’s ability to create the wealth that we all depend on.

More than any other statistic, the chart explains why Britain is getting poorer. What I’m illustrating here is far more important than the usual GDP figures that we hear about, which suggest that Britain isn’t doing too badly. But GDP is a deeply-flawed statistic, for reasons that are poorly understood, even by (or especially by) those in power.

As I explain elsewhere, GDP, which supposedly gives an idea of a nation’s productive output, is actually a measure of total spending in the economy, including spending on unproductive services such as healthcare, policing, etc, and spending based on credit created out of nothing.

So if more people require medical treatment, or if defence spending is increased – to take two examples from recent events – then it will add to GDP.

But sickness and war are not good for the nation, obviously. Even the cost of education, which is good for the nation, needs to be paid for out of productive industry: the idea being that education increases the productivity of the workforce (which is true up to a point, at least, though in reality many other factors come into play here, such as the uses that education is put to).

Some economists argue that spending on healthcare also increases the productivity of the workforce, though in most cases this is not really true, because the majority of health-service users are unproductive anyway (ie, they are either retired or engaged in non-productive activity).

We see in the chart that Britain is the only one of these major economies to show a decline in industrial output per person over the last half-century or more. (I have included Switzerland because, while not a major economy, it is representative of the wealthiest nations, in per-capita terms).

The chart also shows how those countries that invested heavily in productive industry during this period – in particular Japan, South Korea and, most recently, China – have seen the biggest rise in wealth, even if, as in Japan’s case, this rise hits some kind of limit (as we might expect, for reasons explained here).

The reason Britain is doing so badly now is that, beginning in the late 1970s, it has taken the opposite route to most other nations, in that government policy over this period has encouraged the financialization of the economy, which in turn has led to the corresponding trend of de-industrialization. There is a major failure of policy here, in that financialization has not led to increasing investment in production: quite the opposite, in fact: Investors, or their money managers, acting as self-interested individuals (as encouraged by the laisez-faire free-market approach of successive UK governments) tend to take the short-term route to quick profit (ie, through speculation in shares, derivatives and property, etc) rather than investing for the long-term good of the nation (in real industrial enterprises, infrastructure, and so on).

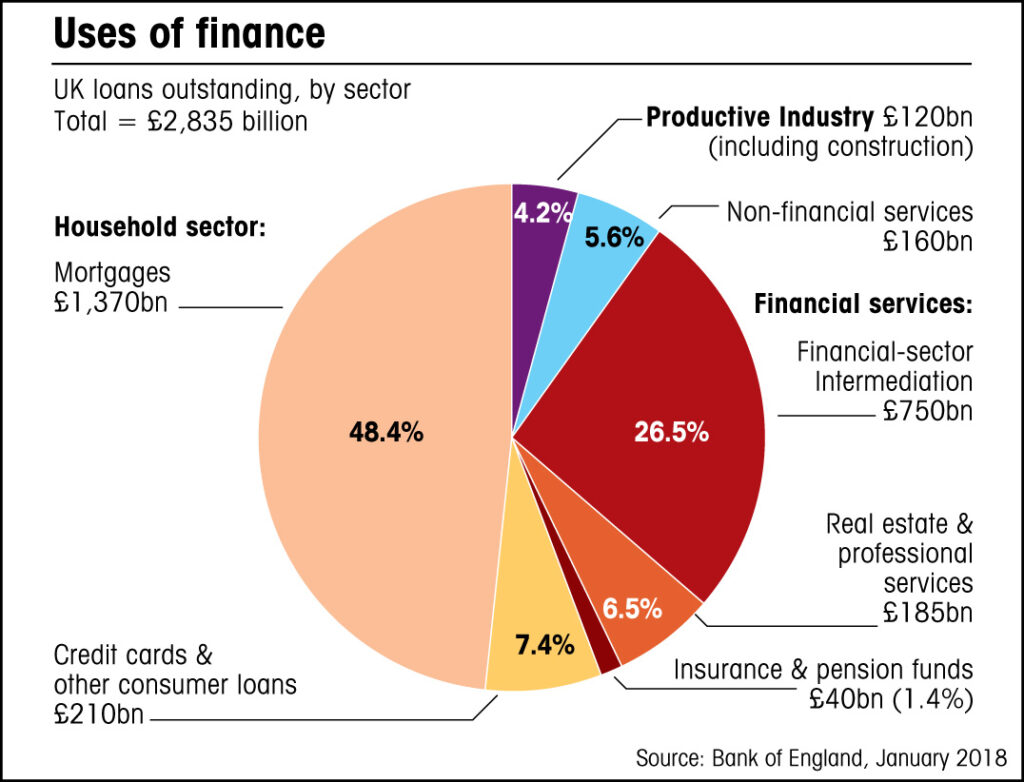

Data from the Bank of England shows that only around 5% of ‘investment’ is directed towards productive enterprise, as my next graph illustrates.

The chart shows UK loans outstanding by broad category of purpose of borrowing (as of January 1st, 2018, though the percentages don’t vary much over time). It refers to UK bank lending, so does not include other sources of business funding, such as bond issues, but a previous report looking specifically at business investment, ‘Bank of England Discussion Paper: Understanding and measuring finance for productive investment’, published in April 2016, drew the following conclusions::

“Only 1% of the proceeds from corporate bond issuance are explicitly stated as being used for investment, with 70% used for ‘general corporate purposes’. Arguably some of the latter could also be used for investment.”

The report goes on to say that: “Only five percent of gross syndicated lending is reported as used for investment … The vast majority of syndicated loans were used for corporate restructuring and mergers and acquisitions.”

And in conclusion: “Overall, the data suggest that only a small fraction of external finance is used for investment.”

Not everything should be left to the market

British policy over the past three or four decades has been based on free-market principles, and the market says that Britain has become uncompetitive when it comes to making a lot of the goods we need, especially with regard to heavy industry: other nations can produce things more efficiently, whereas our competitive advantage is to be found in finance and associated business services.

But policy that relies on free-market principles to guide investment and drive the economy ignores certain basic facts about wealth creation, facts that countries such as Japan, South Korea and China understand. In particular, the need for a nation to support itself through industrial production.

This is not to say that we must produce everything we need, just that we must produce enough wealth to enable us to trade some of it for the necessary goods that we are not producing ourselves.

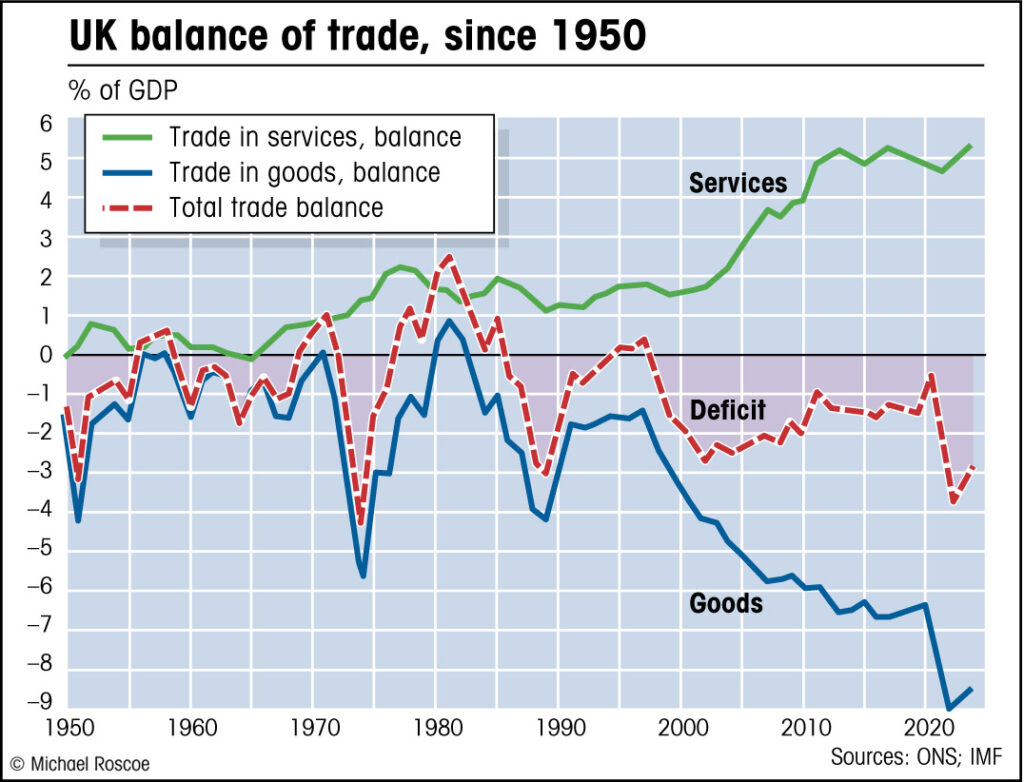

So in Britain’s case, we would need to export enough in financial services to pay for all the goods we must import because we are not producing them here in the UK. But as my next chart shows, this has not been happening in recent decades: the trade surplus in services has not kept pace with the rising trade deficit in goods, and consequently the UK has an increasing trade deficit with the rest of the world. (In fact it has never happened: Britain used to export more goods, so was less reliant on services.)

Why is this? Why can’t Britain sell enough services abroad to pay for the goods we import? The full answer to this question involves an understanding of the relationship between work, wealth, money and values, all of which I explain in my book. But a relatively simple answer would go something like this:

The creation of wealth involves the transformation of the natural wealth of the earth into the products that we all need, both for survival and also to increase our prosperity: food, shelter and the manufactured goods that improve our lives. Money is not wealth, it is merely a token representation of the wealth we produce through our labour. To understand that this must be so, one needs only to accept this fact: that money can be created out of nothing (banks do this all the time), but real economic wealth requires real labour, whether human or mechanical, working on real materials. (As I said, I explain in my book why this must be so.)

Another related fact is that economic value is a function of the ‘usefulness’ of the product. This usefulness is directly linked to the satisfaction of our needs.

All of this means that services, financial or otherwise. are entirely dependant on production. Services are secondary to production both in terms of order (production must come first) and also in terms of value: the true economic value of a service is directly related to its contribution to production.

When it comes to the financial and associated business services that Britain specializes in, the following weakness becomes apparent:

The customers for these services must already be wealthy, and their wealth must ultimately have come from natural resources and/or production (hence the UK’s reliance on oil sheiks, oligarchs and the new billionaires of the east).

The vast majority of the world’s people will never buy these services from Britain, even when they become reasonably well off. When people do need to use banks (or insurers, law firms, etc) they will do so locally.

Which brings us to another problem with relying on services: unlike the production of technologically complex machinery, services do not require great expertise built up over many decades; they are relatively easy to provide locally, and most of them can’t be exported anyway.

Consequently, relying on the export of services to pay for the import of goods puts Britain in a precarious position: the appeal of London to the world’s wealthy could decline at any time, and anyway it is not enough. Everyone need goods, but most of us can do without most services most of the time, and those that people want they can provide for themselves.

See about page for contact details.