The battle against global warming will be lost if we can’t accept the obvious fact that there are limits to growth. While there is room for argument about where these limits might lie, it is clearly absurd to suggest that growth in wealth per person, as measured by GDP per capita, can keep on rising forever, at least in real terms (ie, allowing for inflation: GDP can obviously keep rising in terms of money that is forever decreasing in value).

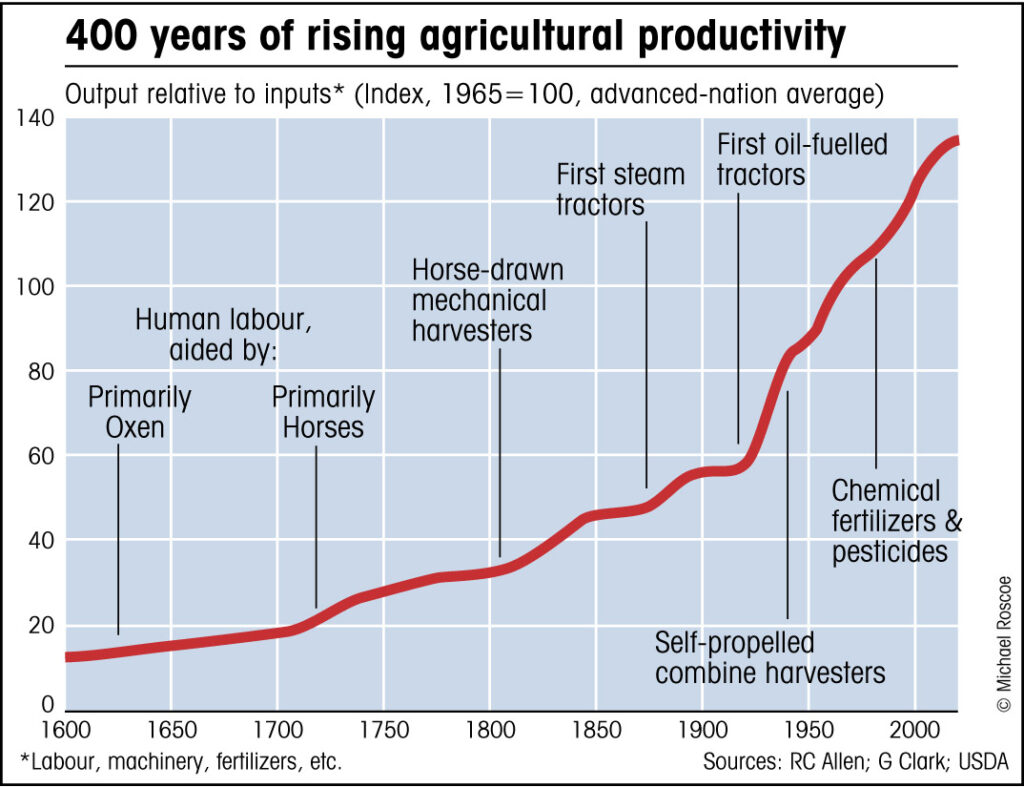

For thousands of years the wealth of human societies was limited by the struggle to provide enough food, a labour-intensive process that took up most of the available time and energy. Total wealth increased slowly with improvements in agricultural productivity, brought about by the invention and development of tools, the harnessing of animal power, machines such as windmills, better land use, etc (as shown in this chart). But until relatively recently, only the wealthy elite – the landowners – saw much benefit.

It was not until the Industrial Revolution that the development of the steam engine set in motion a sequence of self-reinforcing innovations that in turn, throughout the nineteenth century, and on into the twentieth, resulted in dramatic improvements in industrial productivity. The energy released from burning coal, and later oil, when powering machines, multiplied by many times the capacity of human labour to transform raw materials into the products that increase the wealth of society.

This quest for ever-greater productivity and growth, however, must have its limits, just as the agricultural societies of the past had their limits. One such constraint might be the using up of finite natural resources. Another might be related to global warming, as we confront the fact that burning fossil fuels is destroying our environment.

But even supposing resource constraints and environmental issues can be overcome, and that we manage to replace all fossil-fuel power with renewable energy, enabling the latest machines to produce almost unlimited quantities of goods, there is still a less obvious reason why wealth accumulation must at some point reach a limit. Wealth is related to value, and value (in economic terms, at least) is always a function of usefulness. So the production of goods that serve no useful purpose would obviously be a waste of resources: no value would be created.

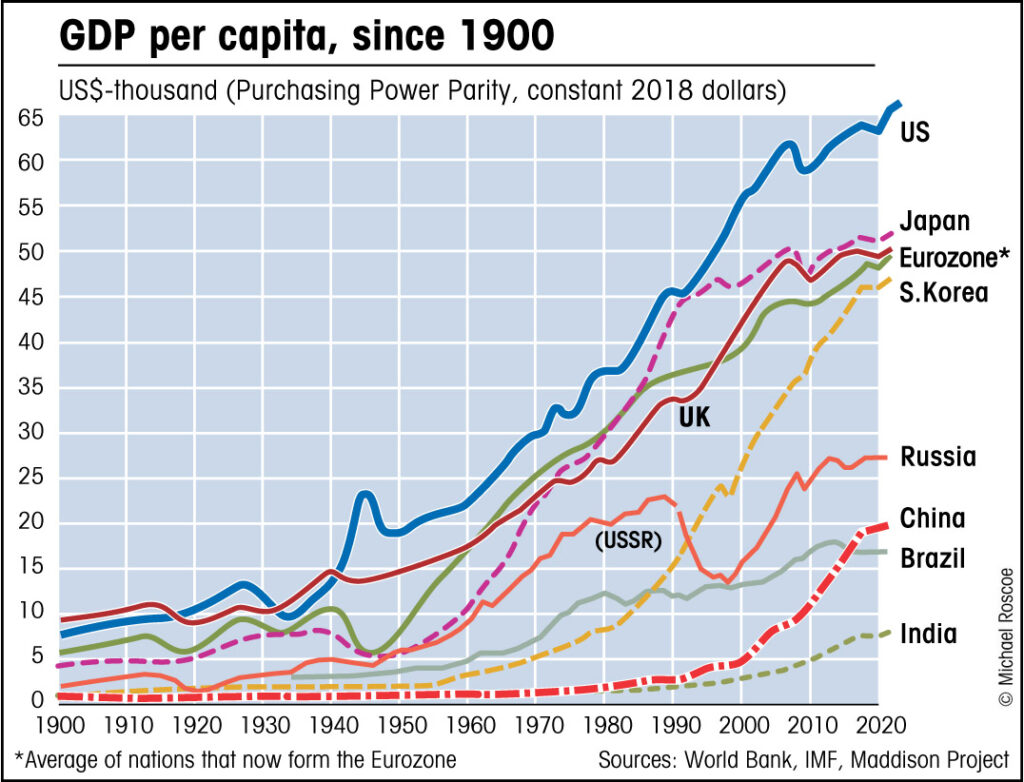

The potential for growth is therefore greater for poor countries than for rich, because poorer societies have greater need. Nations become wealthy when they produce more of the goods that improve people’s lives, from basics like food and clothing to the cars and other machines and appliances that make us more productive, along with decent housing and public infrastructure. That is how Britain and the US, followed by Europe and Japan, became rich.

But as a nation becomes wealthier and more needs are satisfied, there is a tendency towards the manufacture of goods that are less essential, and therefore must have a lower ‘use value’, even if they might have a high market value. For example, nobody needs luxury goods, by definition; they are produced because rich people have an excess of money and like to spend it on things that supposedly enhance their comfort and status.

We can’t all be rich

I have already made the point that the very wealthy haven’t really earned most of their wealth, because nobody can work hundreds of times harder than the average person. The rich have, through various forms of ownership of capital and resources (agricultural land, real estate, corporate shares, loanable funds, etc) appropriated wealth produced by workers elsewhere, be it locally or abroad.

If this wasn’t the case – if, in fact, the world was much more equal and everyone had to truly earn their wealth – then we would soon find that, although some people would obviously work harder than others and therefore earn more, everyone would at some point reach a stage where they no longer found it worth their while putting in the extra effort, just to be able to buy more stuff they didn’t really need.

And this level of prosperity – the point at which we have all we need for a comfortable life, and therefore place a higher value on leisure time than on further increasing our income – would seem quite modest in comparison with the fortunes of today’s multi-millionaires, because values would not have been distorted by an excess of unearned wealth in the hands of the few (ie, those who’ve made money from their money, rather than from real work). We might still compare ourselves to others, but the difference between the average and the richest would be far less than it is now: we would be more easily satisfied with our lot.

It is possible that, in the more developed parts of the world, we are already close to this limit, or have actually exceeded it, in terms of average wealth per person, and that this is the reason why advanced societies today are finding it so difficult to raise growth levels further, despite making it their main priority.

This is not to say that the poorer countries of the world can’t raise their living standards: they obviously can and, in many cases, have been doing so. But it might account for the so-called ‘middle income trap’, whereby developing nations that have managed to raise their level of GDP per capita from around one tenth that of the US (for example) to around half the American level, find it difficult to close the gap further. Only a few countries have avoided this trap, and they are all relatively small nations in which governments invested heavily in industries that produced goods for export, such as South Korea and Taiwan.

Ignoring for a minute the environmental consequences, would it be possible, in theory at least, for all the world’s citizens to reach a per-capita income level similar to that of, say, Switzerland? I don’t think it would.

I explain in my book how the US and Britain, through ownership of global corporations and the provision of financial services, capture a significant portion of the wealth produced elsewhere. Switzerland has been even more successful in this regard. The Swiss provide discreet banking services to the world’s ultra-rich, as is well known, and they also earn a good income from real industry, exporting precision machinery and other manufactured goods around the globe, thus making the most of both the Anglo-Saxon and German models, one might say. And they’ve been doing all of this for a long time, while keeping out of the wars that have destroyed wealth in neighbouring countries.

In addition to these more acknowledged sources of income, Switzerland is also home to several of the world’s biggest commodity-trading firms, despite having few natural resources of its own. This trillion-dollar trade constitutes around 4.5% of Swiss GDP (banking is around 10%).

All this has made the Swiss, on average, considerably wealthier than Americans, even; almost up there with the citizens of Norway and Qatar, both of which export huge quantities of oil and gas and spread the proceeds amongst small populations.

If such societies are benefitting from wealth produced elsewhere, however (which is undoubtedly the case), it stands to reason that not all nations can follow this path.

Where might the limit lie?

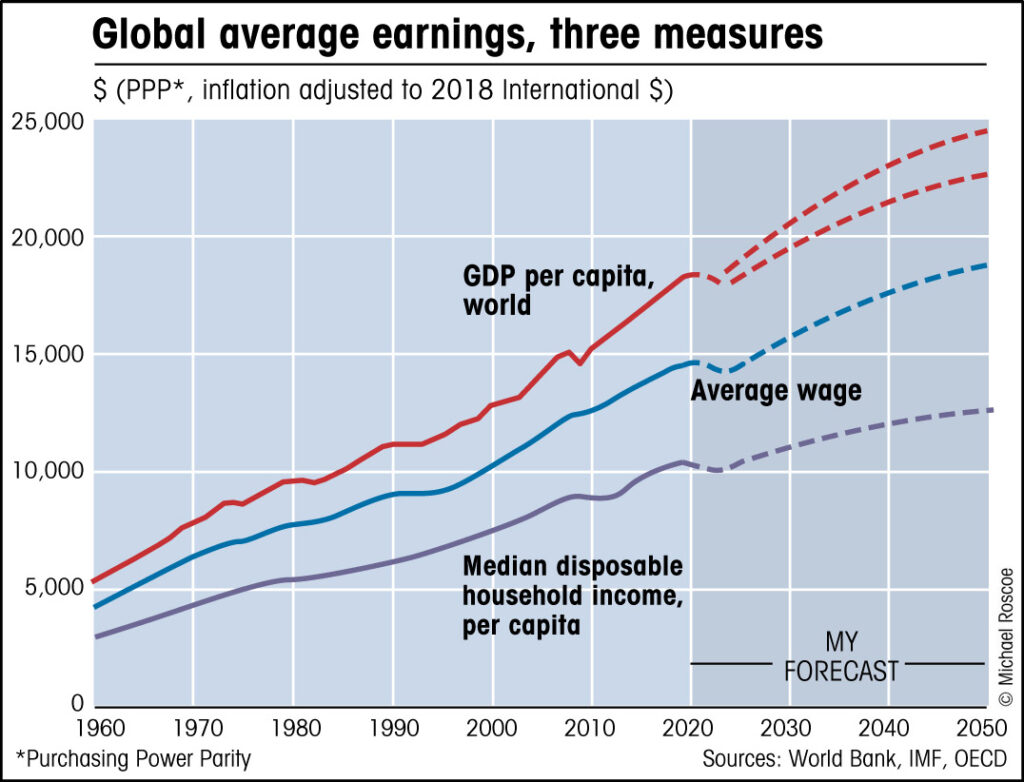

The average GDP per capita for the whole world was somewhere around $18,000 in 2019, or just under a third that of the US (roughly 30% of the US figure, in terms of purchasing-power parity, or PPP). My guess would be that, in a world of more equal opportunities in which everyone earned closer to their true worth, in terms of the value they are creating through their work, so that prosperity could be shared more evenly, and therefore more widely, this average could be raised to something like $25,000.

Although GDP per capita is not the same thing as the average wage or household income, there is some correlation between all three measures of earnings, as seen in my next chart.

An average global GDP per capita of $25,000, under conditions of greater equality, would mean that the average wage would be in the region of $18,000, while median household disposable income (per capita, after tax and including benefits) would likely be around $13,000.

At this level of wealth creation worldwide, spread fairly evenly, earnings would be such that most people could afford the things they really needed, and demand for further goods and services might therefore begin to ease off.

So the limits to growth are likely to mean that, on average, GDP per capita for the whole world cannot rise much above a level somewhere around that of, say, Mexico or Turkey today, or roughly midway between China and Russia. But in a more equal world, this should be enough for a decent life for the vast majority of people, for we would be making better use of wealth if it was spread around more evenly.

As society develops and we become more prosperous, continuing technological advances bring fewer rewards, as fewer improvements are needed: we reach a plateau with regard to our potential. For example, ships, trains and motor vehicles all brought gains to productivity by improving our ability to transport goods and people. But in all cases these gains levelled off, and in some cases even reversed somewhat, as the increased wealth of society brought new problems, such as traffic congestion and pollution, or because the costs of further advances outweighed the benefits, as with supersonic passenger flight.

We see the same thing with digital technology: big gains from computers, broadband internet, etc, as they first become widely used, but less so with each new development. In other words, advances in both technology and productivity, and hence wealth creation, face diminishing returns, because the value added to society declines in proportion to the satisfaction of wants, or needs.

Progress and priorities

So now we face new problems related to climate change. The best way we can improve our lives is not by producing ever more stuff, flying faster, landing on Mars … The priority now is to give our grandchildren a better chance of survival and the prospect of a decent future in a more equal world. This is where we need to invest our resources and add value through innovation, and that is why some kind of Green New Deal is so essential. And as with the original New Deal, it will take the full power of the state to see it through, only this time it needs to be on a global level.

So here’s the good news. Even if the concept of ‘green growth’ is indeed an oxymoron, we shouldn’t let that worry us too much: we can forget about GDP figures, and concentrate instead on improving our environment. The key to doing this successfully is to invest in the things that really matter, while acknowledging the critical nature of the relationship between natural resources, work, money and wealth: a relationship that has in recent decades been neglected and corrupted by the financialization of the economy.

The greed-is-good mentality that drives the Anglo-Saxon model is based on the argument that self-interest powers the economy, and that individual self-enrichment should therefore be encouraged by keeping taxes low and, whenever the market sees fit, compensation high. This limited viewpoint did at least have a certain logic to it in the days when most entrepreneurs went into productive industry, and when a good portion of that industrial wealth was spread around society via factory wages.

But in recent decades this has not been happening: those with the best qualifications and the brightest prospects have been lured into finance by the promise of rich rewards, their talents directed towards (and wasted on) the business of making money from money through speculation and asset-price inflation. While a lucky few have hit the jackpot, the majority of people, and society as a whole, have paid a heavy price.

Time for a new model

Sky-high levels of debt, rising inequality, reduced disposable incomes for the majority, the disaffection that brought us Brexit and Trump: such are the consequences of the Anglo-Saxon model of financial capitalism. Add to this the knowledge that we must now end our reliance on fossil fuels, and we can see that tackling climate change and solving our economic problems must go hand-in-hand.

As already explained, the rich nations became wealthy by producing more of the goods that improved people’s lives, which for a few decades resulted in a self-feeding cycle of increasing productivity and prosperity. Now that the more advanced societies have attained a level of wealth at which all their citizens could, if only the wealth was spread more evenly, live comfortable lives, this cycle appears to have reached its limits, or even exceeded its limits by living off credit.

Future improvements will come not from producing ever more stuff, which has become unnecessary, but from spreading wealth more evenly whilst also avoiding the worst effects of climate change, and indeed from eliminating the causes of global warming. This will be the key to future value and to future wellbeing.

We must start by reforming the monetary system and reversing the process of financialization, so that national resources can be directed towards the things that matter. Such reforms will enable the creation of debt-free money for investment in the long-term solutions that will address the challenges posed both by inequality and by global warming, as well as helping our economy to recover from the effects of shocks such as wars or pandemics.

(This is an extract from my book, ‘From Brexit to Fixit: Why Britain is Getting Poorer and What We Should Do About It’. Please see ‘about’ page for details.)