Why are there so few decent jobs now?

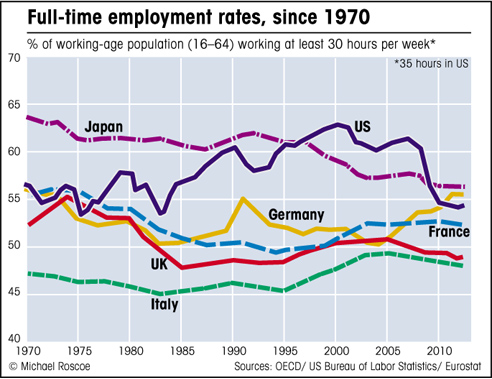

One of the biggest problems facing the world today, along with global warming, is a decline in the number of decent jobs. By ‘decent’ I mean reasonably well paid, full-time (at least 30 hours per week) and preferably of use to society as a whole, either because the work is in a real wealth-creating industry, or the worker is performing a service that adds value to the community.

In the book I explore the idea that we don’t need to work as much anymore because machines can produce most of the stuff we need, and therefore we can spend more time relaxing and enjoying the fruits of the labour of all those robots.

Although this is theoretically possible, there are several reasons why it doesn’t work, except perhaps in a closed system where the state controls the raw materials and the means of production and the people are rewarded for doing nothing.

I show why Marx had to be right when he said that labour is the source of all economic value, and how, in fact, work is the source of all value in our lives. Without work, we have nothing.

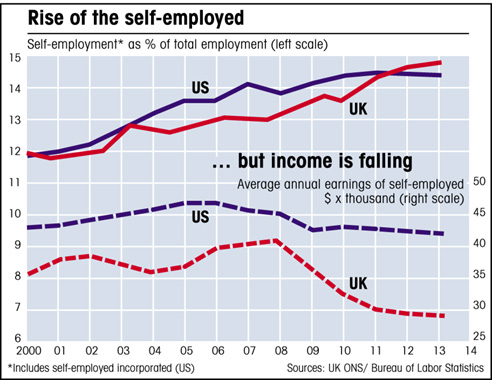

Which is why it is so important that we reverse the trend of declining real employment. I demonstrate how this decline is linked to the financialization of the economy, ever-rising productivity and the inequality that results from these related factors, and why digital technology is making things worse.