Why the US will stay on top

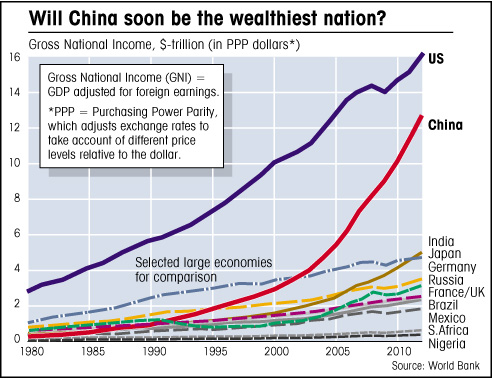

Much has been said about the likelihood of China overtaking the US to become the world’s largest economy in the next decade or so, as this chart shows.

But although China might become the world’s biggest economy in terms of industrial output, it is highly unlikely that nations such as China and India will ever approach the levels of wealth seen in the US and Europe. Ignoring the fact that an increase in consumption on such a massive scale – the two nations account for 2.5 billion people, compared to 800 million for the US and Europe combined – would surely be disastrous for the environment, the economic growth required to boost individual wealth to such levels cannot be sustained for more than a few years without the economy overheating. China’s rapid growth is already slowing down, as wages and productivity rise along with prices, and demand eases off both within China and throughout the world.

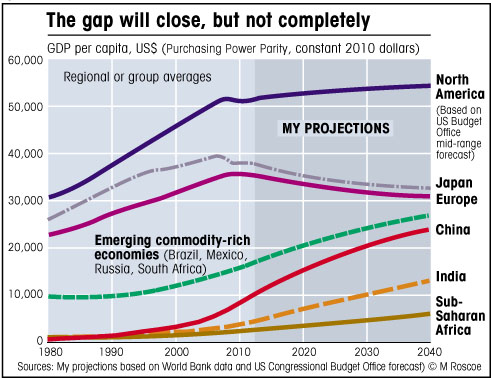

It seems far more likely, and far more desirable from an ecological viewpoint, that the developing nations will gradually close the gap on the rich world through a combination of continuing moderate growth on their part, accompanied by a decline in overall wealth levels in much of the rich world.

In the following chart I have plotted, with a little help from the US Congressional Budget Office, what I think is a likely scenario for this adjustment in relative wealth.

While it seems inevitable that Europe and Japan will see a permanent decline in wealth, the prospects for the Americas generally, and North America in particular, seem less bleak. This is due mainly to the ratio of natural resources to the number of people. There has always been a direct relationship between natural resources and wealth, but whereas in the past Europe grew rich by plundering the natural wealth of colonized lands, these days it has to pay the going rate for the raw materials of industry, most of which it must import, and this rate is bound to keep rising as resources become scarcer. So it follows that those bigger nations with abundant natural wealth and not too many people will most likely benefit, as we have already seen to varying degrees in Canada, Australia, Brazil and Russia.

The US has two big advantages over Europe. As well as having a much greater abundance of land and mineral wealth, it also has demographic advantages related to a younger population, and both of these factors will give it greater flexibility when it comes to budget balances and debt repayment.

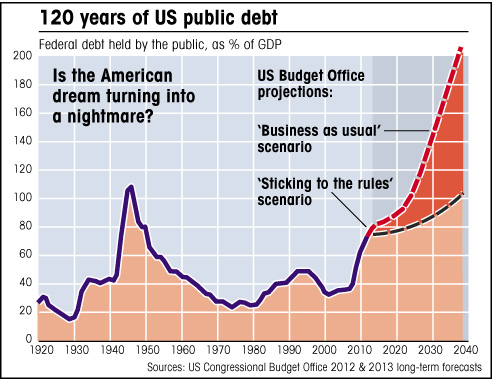

There is a big question mark here, however, because the US debt burden could get a lot worse over coming decades, depending on what action the government takes. My next chart comes from a 2012 report by the US Congressional Budget Office, which analyzes the long-term outlook and comes to some rather startling conclusions.

Obligations that won’t be met

The chart shows how US debt is set to explode unless the government can cut spending and raise taxes (which as I write it is trying to do, but the rival politicians can’t agree on much). In the worst-case scenario envisaged by the Budget Office, which means carrying on the way things have been going over the last few years, “The reduction in GNP would lie in a broad range around 4% in 2027 and in a broad range around 13% in 2037.”

In other words, the economy is set to contract significantly because of the debt burden, entering a vicious spiral of job losses, falling incomes, inflation and rising interest rates, all of which will make the problem far worse. The report concludes:

“The ageing of the US population and the rising costs for healthcare mean that the combination of budget policies that worked in the past cannot be maintained in the future. To keep deficits and debt from climbing to unsustainable levels, as they will if the set of current policies is continued, policymakers will need to increase revenues substantially above historical levels as a percentage of GDP, decrease spending significantly from projected levels, or adopt some combination of those two approaches.”

This is quite a dramatic admission from a government office, one that is also applicable to some European nations, though they are less inclined to state the issue so clearly. The report is making the point, quite simply, that the west is going to get poorer. Without going so deeply into the fundamentals, the authors are confirming many of the points I’ve been making in this book; we have been borrowing substantially from future earnings, and one way or another we’ll have to repay those loans.

So the US is faced with currently unsustainable social-welfare obligations; it can’t meet future pension and healthcare promises. Much of Europe is in the same position. These promises will be broken.

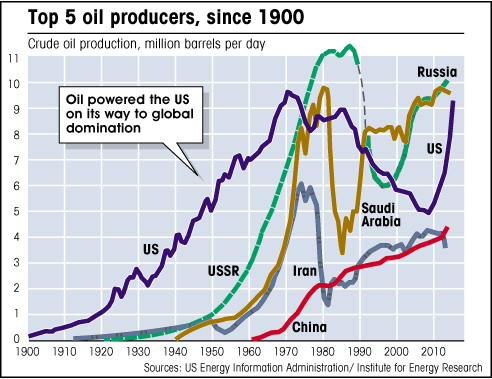

The US, however, has better prospects for solving this problem, partly because its economy could still show spurts of growth, helped by new oil and natural gas reserves made possible by its development of ‘fracking’ technology, as explained in Chapter 17. The US is back in the top league of oil producers, and as I make clear elsewhere in the book, oil is the biggest source of wealth in this world.

The resulting cheap natural gas is already attracting businesses from other nations, as the US becomes once again a competitive place to make things. China will lose its cost advantages as wages rise; the balance is likely to swing back in America’s favour, especially if US wages continue to fall in real terms.

Despite environmental concerns, fracking is the only real boom industry on the horizon right now, and the US will most likely be the biggest beneficiary, thanks to its technological lead in the field. From an ecological viewpoint this might not be good news, but as far as the US economy goes, it probably is.