Even in difficult times, we can still be happy

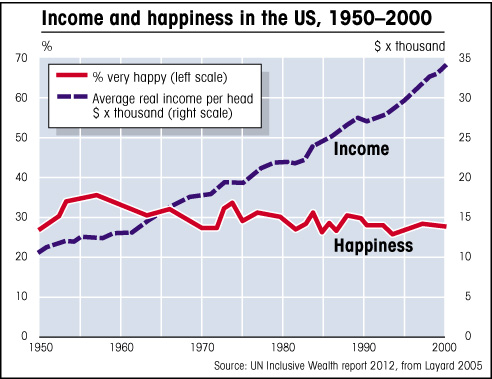

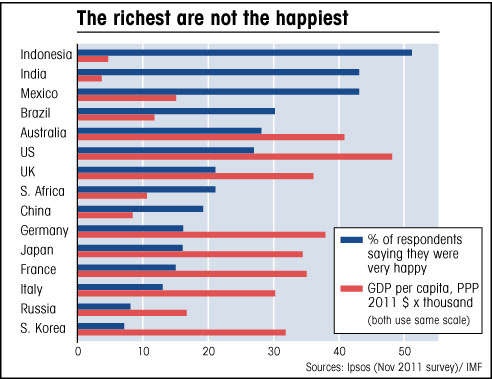

The end of growth doesn’t have to mean the end of prosperity, not if we spread wealth more evenly and re-evaluate our perception of prosperity.The good news is that happiness isn’t directly dependent on material wealth, as my following two charts show. Various surveys over recent decades have come to the same conclusion; that once we attain a level of wealth sufficient to live on, with enough money to keep us out of poverty, then increasing our income further doesn’t necessarily increase our happiness. In fact, as my next chart shows, happiness can actually fall as income rises.

This is because our expectations increase along with our wealth; the more we earn, the more we want; the less easily we are satisfied. And as we try to maintain the high income to which we become accustomed, the higher our stress levels rise.

Most studies into the relationship between income and happiness, or wealth and well-being, have shown little correlation between these two important aspects of life, but they have shown a significant correlation between income equality and happiness.

As the above chart shows, some of the poorest countries have some of the happiest people, just as long as the wealth is spread reasonably fairly. Obviously there are other factors one must take into consideration, such as climate and culture and the way people respond to such surveys, but the important point as far as this investigation is concerned is that a reduction in average incomes doesn’t have to mean a decline in well-being, and if such a reduction can be accompanied by greater equality, could even lead to greater happiness.

The key is how reality conforms to people’s expectations, and expectations increase with wealth, often more than the actual standard of living. Once certain basic necessities are provided for, greater income leads to greater aspirations, and these aspirations often become unrealistic; our satisfaction relative to spending decreases. It is likely also that the kind of people who aspire to more are also the types who are less easily satisfied.

As we become wealthier we also become more concerned with our place in society; we compare ourselves to others, and of course there is always someone around the corner who is apparently better off than us; the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence, as it were. We resent the rich flaunting their wealth, reminding us how unfair life can be. But we shouldn’t envy them – they are probably dissatisfied with their own lives anyway. And as the Stoic philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome understood, there is no point in worrying about all the aspects of life over which we have no control. Better to heed the advice of Seneca: If what you have doesn’t satisfy you, then however much you possess, you will always be miserable. Or better still, Epictetus, who pointed out that the best way to achieve happiness is to lower one’s expectations until they meet with reality.

Cause and effect are not obvious when it comes to such a vague concept as happiness, but the evidence suggests that equality is much more important than outright wealth, at least in monetary terms. Prosperity is linked to other things besides money; health, relationships, environment, work – unemployment is one of the biggest causes of unhappiness, not surprisingly.

Another advantage to redefining prosperity is that all the arguments against higher taxes and greater regulation of finance and so on – that we will discourage free enterprise by limiting the motivation of entrepreneurs to create great wealth, etc – these arguments lose what little credibility they might have had, once we accept that growth is no longer desirable, that in fact we need to cut our consumption of resources anyway. The big challenge now is how to improve our living standards in more subtle ways than simply consuming more and more of the world’s finite resources and warming up the world, threatening to wipe out humanity in the process.

While it will still be desirable and even essential to encourage investment in real industry, and also to encourage entrepreneurs to find solutions to problems through technology, we shouldn’t have to rely on the motives of self-interest and greed.