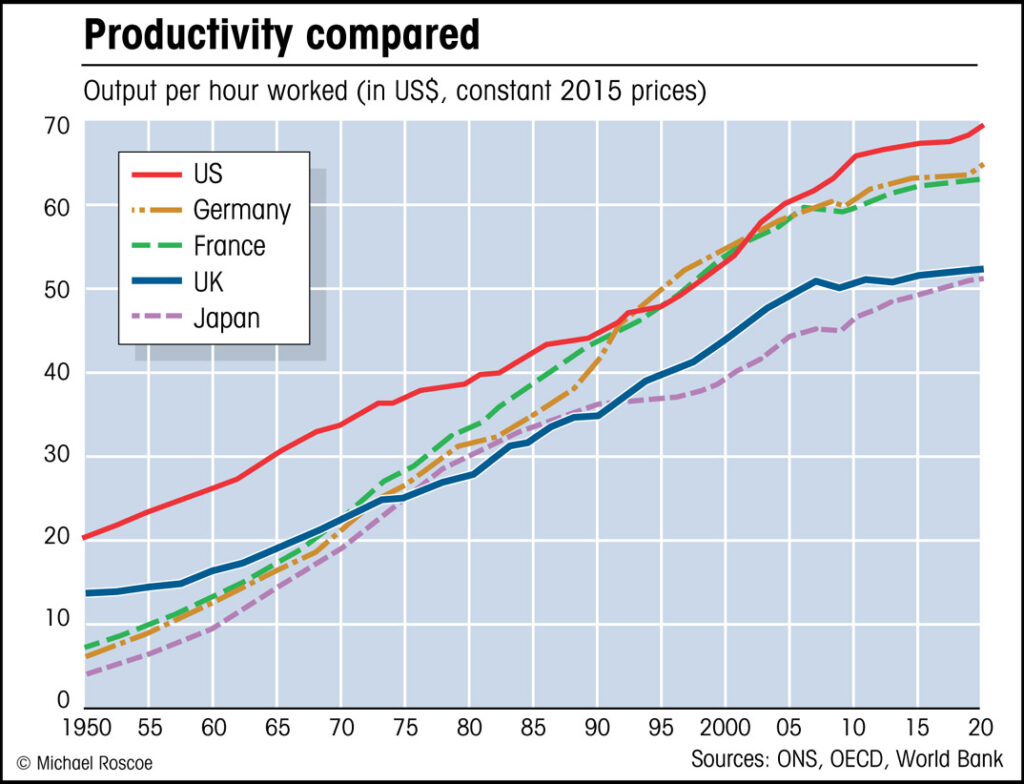

Britain’s relatively poor productivity record, which governments have been struggling to improve for years, is considered something of a mystery by economists and policymakers alike, as this quote from a report by the UK Office for National Statistics (from October 2017), suggests: “The UK’s ‘productivity puzzle’ – the difference between post-downturn productivity performance and the pre-downturn trend – was almost double the average across the rest of the G7.”

The puzzle refers to the fall in productivity since the crash of 2008, which affected most economies but was worse in Britain, as the chart shows. As the Financial Times reported in the same month, after the Treasury was forced to admit that its UK growth forecast was likely to prove too optimistic (yet again), “There is much debate and little agreement about the reasons for the UK’s productivity woes.”

In simple terms, productivity is defined as economic output relative to inputs, and is therefore a measure of efficiency: the ability to produce more goods from the same inputs, in terms of labour in particular, but also capital and raw materials. Productivity is an important concept with regard to wealth creation and the development of society generally, and is directly linked to innovations in technology and the way we work: the more we can produce with a certain amount of effort – one hour’s labour, for example – the better off we will be. So if we want to raise wages relative to other prices, we must raise our level of productivity (and distribute the proceeds amongst the workers, of course, not just the corporate owners).

A 2019 ONS report stated: “We have estimated that if productivity had grown in line with its long-term trend, average market sector wages would have been over £5,000 higher in 2018 than were observed in reality.” (UK Office for National Statistics report: ‘Productivity economic commentary: January to March 2019’)

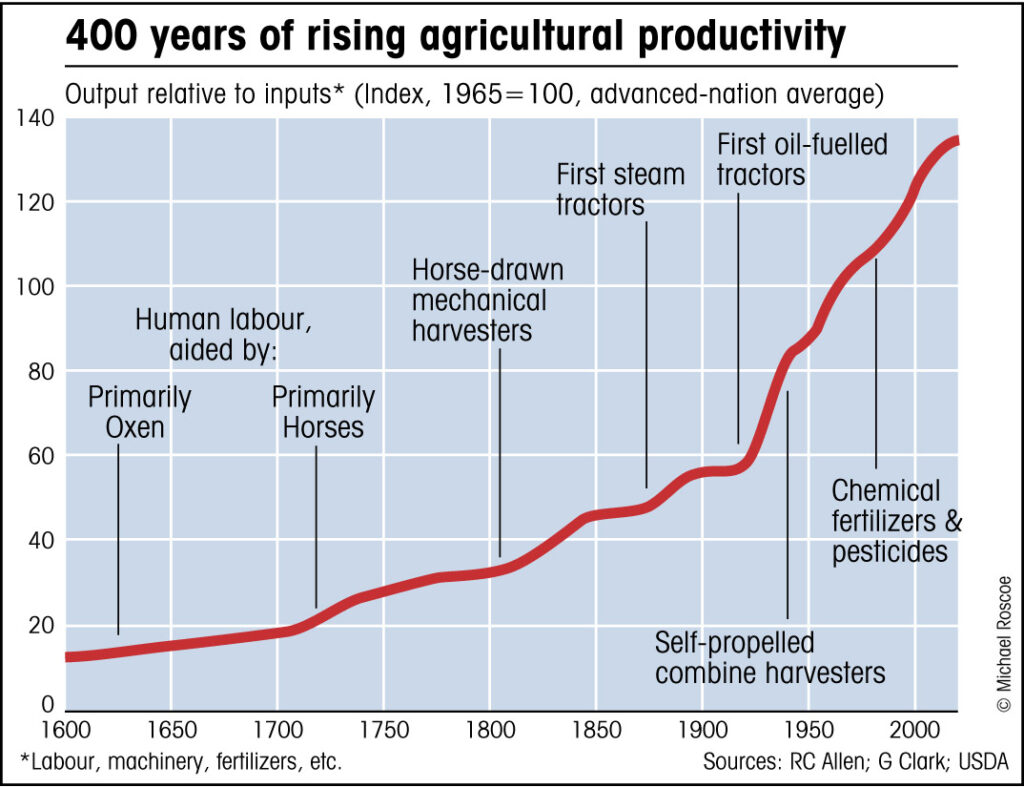

Historically, productivity has improved in stages following technological advances and subsequent changes to working practices. Agriculture provides a good example. Following the development of the plough, the invention of the farm tractor and machines for planting and harvesting and so on, along with new techniques in crop rotation and plant selection, agricultural output relative to inputs has increased dramatically over the centuries, as shown in my next chart.

The Industrial Revolution, which only became possible after those previous gains in agricultural productivity freed up thousands of workers, brought similar patterns in the manufacturing sector. Human labour was augmented by machinery that increased industrial output, making use of energy derived initially from the power of hillside streams (using water wheels), then steam engines powered by coal, followed by the development of electricity and oil-fuelled engines.

But the actual measurement of productivity, especially in a modern service-dominated economy, is problematic, partly because of those issues mentioned elsewhere regarding GDP (with sales being used as a proxy for production, etc), and partly because inputs are also difficult to measure accurately. The most important input is labour, and the usual way of comparing productivity between different firms, industries or nations is to look at the output, in terms of gross value added (as used to measure GDP) relative to the number of hours worked.

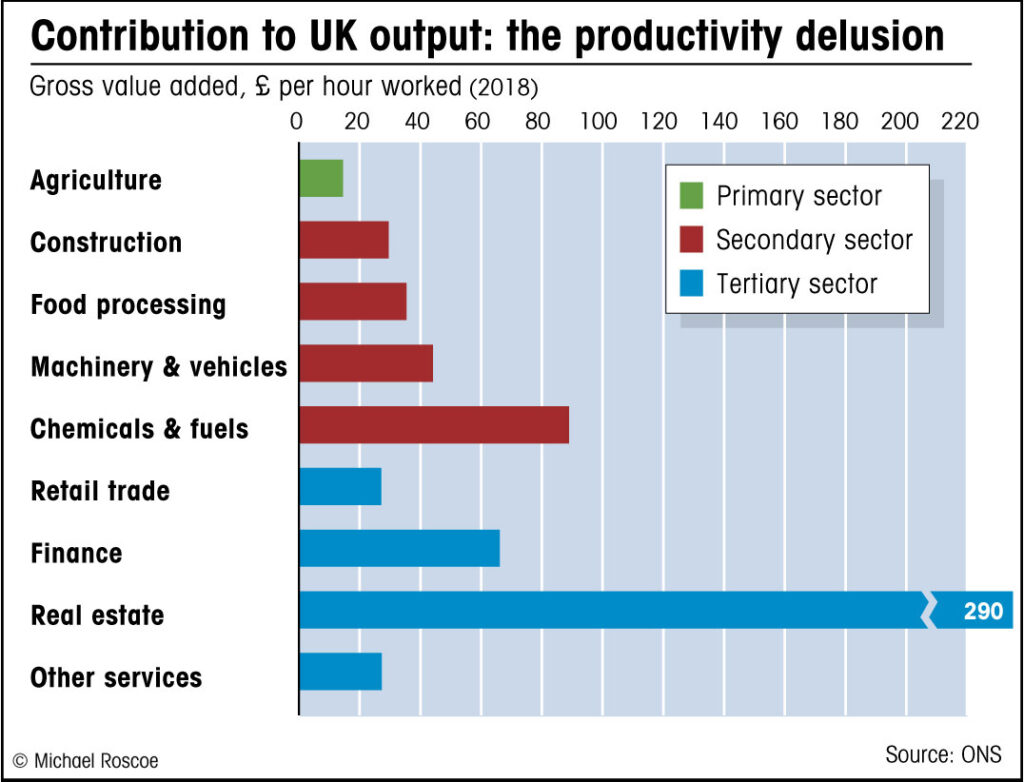

Such methods, however, can be seriously misleading. For example, the following chart shows contributions to UK productivity by sector, in terms of output per hour worked, according to data from the Office for National Statistics. The figures imply that estate agents are ten times as productive as farmers and builders and five times as productive as factory workers. This, of course, is complete nonsense.

What the figures are actually showing is that estate agents, and the whole property-dealing sector generally, shift large sums of money around relative to the number of people employed in the business. This is not so surprising: it only takes a few office staff to buy and sell property worth millions of pounds. But it has nothing to to with actual productivity: the production of buildings is done by the construction workers, obviously.

The problem here is that most economists, especially those advising the government, conclude from these figures that the financial sector, along with all those super-productive estate agents, is the driving force behind the British economy. This misunderstanding can have serious consequences. Because such financial transactions boost GDP out of all proportion to their real value to society (which, in the case of estate agents, is related to their usefulness in helping people buy and sell property), government priorities are biased towards the wrong kind of economic activities: we should be supporting the real producers, the farmers and builders and manufacturers, not the property dealers and financiers.

Puzzle solved?

As for Britain’s poor productivity record in recent years, a big part of the answer is related to over-inflated GDP figures in the credit-fuelled boom years: the long-term trend, which shows rising GDP per hour worked over the three decades leading up to the 2008 crash, was boosted by financial-sector activity based on rising debt levels, not real industrial productivity. Following the crash, and the bursting of the bubble, we have returned to a less-inflated level of ‘output’ (though real industrial output is obviously much lower than GDP figures imply, as explained here).

The first chart gives a clue to another reason for weak productivity growth. Why is Japan, which has one of the most efficient manufacturing sectors in the world, even less productive than Britain?

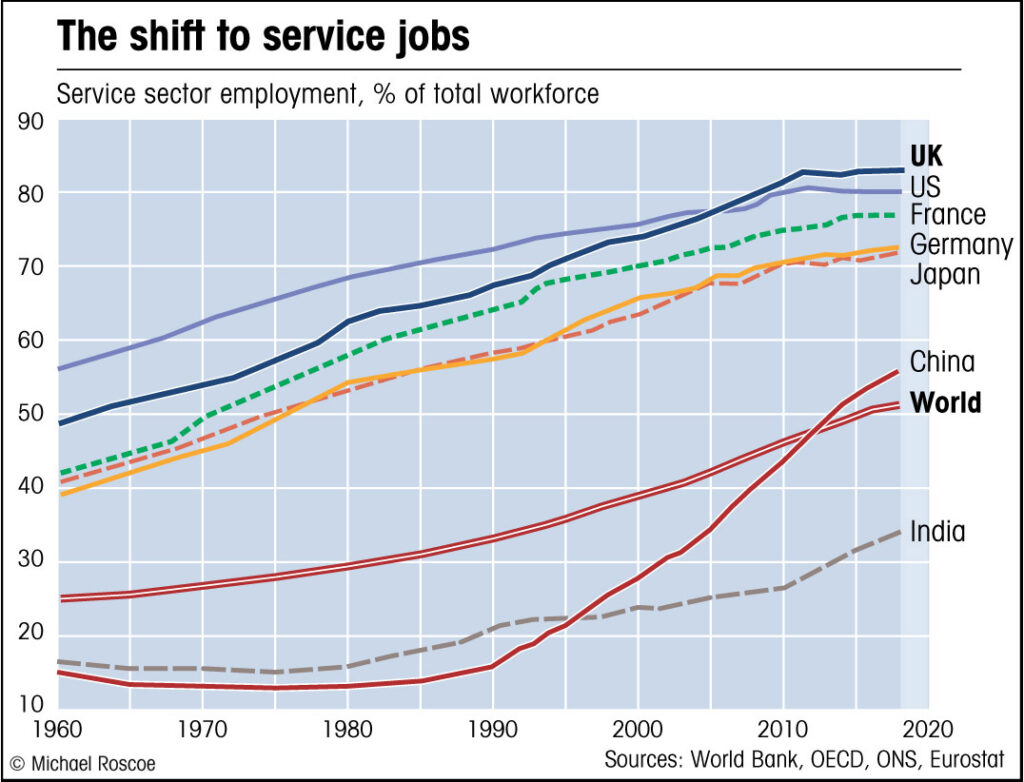

The answer is that the manufacturing sector, though it might be increasingly productive, not just in Japan but throughout the world, represents a decreasing percentage of economic activity relative to the economy as a whole, in terms of both employment and GDP. More and more people are working in less productive jobs, because these are the jobs that are less likely to be automated: most robots are employed in the manufacturing sector.

It just so happens that Japan’s service sector, in contrast to its factories, is the least productive, in terms of output per worker, of all advanced nations. This is because the Japanese value certain traditional practices that in the west we’ve abandoned in our quest for lower prices, such as local shops that provide a more personal service: they have fewer large supermarkets, with less automation, and therefore they employ more retail staff relative to sales. The same principle applies throughout Japan’s service sector, which, although not as dominant as Britain’s, has nevertheless been increasing in terms of employment share, as shown below.

Does it matter?

There are reasons why productivity matters in the industrial sector, because that’s where all the real production takes place, and therefore all the wealth creation, and in a global marketplace for goods, competition ensures that only the most efficient producers survive. So we Brits would be more productive, and therefore better off in terms of earnings, if we’d invested more in real industry.

But when it comes to services, it surely matters less. It doesn’t even make sense to talk about the ‘productivity’ of services, which don’t produce things anyway: what we really mean is efficiency. The efficiency of a waiter, for example, or a hairdresser, shop assistant or whatever, will be related to how quickly they can serve the customers; hardly a critical matter.

What it comes down to is the prices we pay for such things: higher efficiency in services should keep down costs, as it does in manufacturing, but if displaced workers can’t find jobs elsewhere, there’s a price to pay in terms of unemployment. What really matters is how much wealth is produced in total, and how evenly that wealth is spread around.

Suppose we did manage to raise the efficiency of most services by replacing workers with machines wherever possible. Where would the displaced workers find other jobs? Beyond the service sector, there is nowhere else to go. The only reason Britain has not fared too badly in terms of unemployment since the 2008 crash, relative to most European countries, is that the service sector, being less suited than manufacturing to automation, has created thousands of low-paid jobs in healthcare, warehousing, parcel delivery and so on.

We would soon discover, therefore, that a more automated, more efficient service sector would be offset by decreasing efficiency in society generally, because we need jobs both for ensuring distribution of wealth through earnings, and also because work is an important part of our lives, an essential component of human satisfaction and wellbeing.

The whole concept of productivity, when it comes to jobs in services, especially education and healthcare, is surely misplaced. Would you prefer a super-efficient robotic nurse, or would you rather be looked after by a caring human being?

There’s a related moral issue here, too, with regard to our need for useful employment. Although we as individuals don’t actually produce most of the things we require for our own survival, we should at least be putting an equivalent amount of effort into some kind of work, something that adds to the overall good of society – and this includes unpaid domestic work, such as childcare, etc – otherwise we must be living off the labour of others, which can’t be right (unless the ‘others’ are robots: more on this later).

And to some extent this is already happening: the general disaffection that led to Brexit, and also to Trump in the US, was at least partly linked to this decline in productive work, along with the accompanying failure of wealth distribution.

As for those super-productive estate agents, their ‘output’ rises along with property prices, which has nothing to do with either productivity or efficiency (though it might well reduce the productivity of workers who can’t afford a decent home). This brings us back to the same old problems related to the financialization of the economy. The real puzzle is not Britain’s poor productivity record, which is surely to be expected when we’re producing less real stuff: the only puzzle is why anyone would expect anything better from a nation that has become increasingly dominated by financiers, lawyers and estate agents.